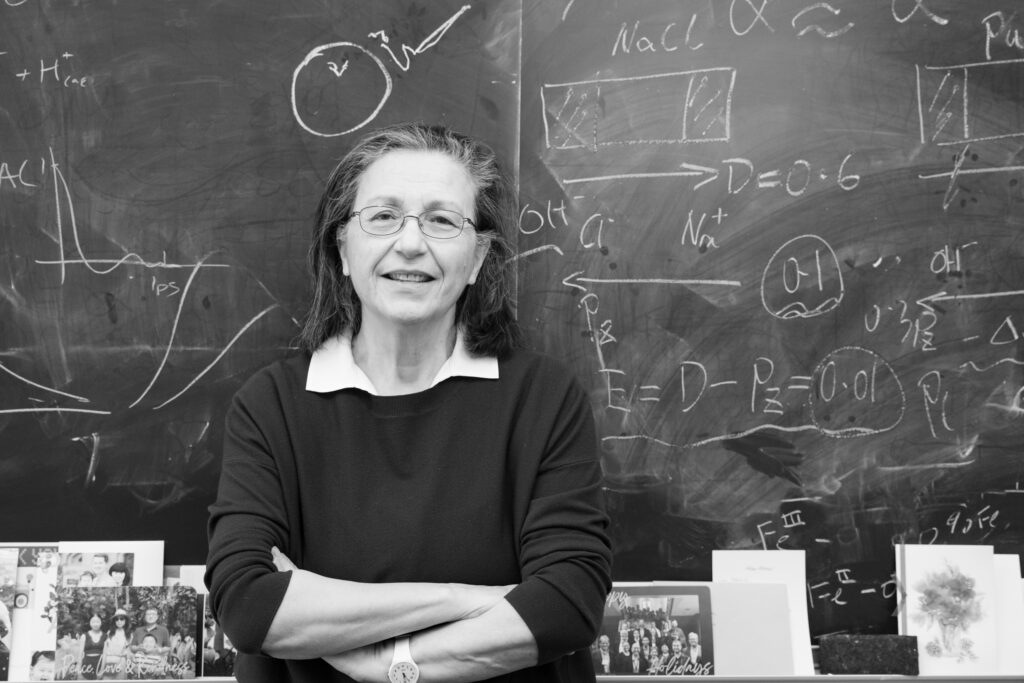

Annabella Selloni, ‘Star in Her Field,’ Transfers to Emeritus Status

The last time colleagues held a retirement party for Annabella Selloni, in another country, back in January, she was asked to say a few words to mark the occasion. She stood up and said three or four.

“I think they might have been a little disappointed. Next time I will at least try to thank the people who came,” Selloni said in preparation for the Annabella Selloni Retirement Symposium at Princeton Chemistry.

The anecdote underscores two things about the understated Selloni, the David B. Jones Professor of Chemistry: one, the retirement thing is not really her strong suit – “Everybody says congratulations, but there is nothing to congratulate …” – and two, she is being celebrated on at least two continents for her contributions to surface chemistry. The impact is obvious, even for someone as sanguine as Selloni.

Colleagues, former students and postdocs, family friends and well-wishers flooded into Frick Laboratory last week to celebrate Selloni’s transfer to emeritus status in July. The Symposium marks her 25 years at Princeton Chemistry and a long career that played out across several countries and in two distinct fields.

The two-day event, “Frontiers in the Chemical Physics of Heterogeneous Interfaces and Beyond,” included scholarly presentations by 20 individuals.

The title mentions both chemistry and physics, which underscores a driving theme of her career. The boundary between the fields has been porous for Selloni since she received her undergraduate degree in physics from La Sapienza University of Rome and followed it up with early-career research in solid state physics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. In fact, it wasn’t until she took a position at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Lausanne in Switzerland in the 1990s that she officially began working in chemistry.

Today, she is recognized internationally as a leading theorist for her extensive work on oxide surfaces.

Asked why surfaces were so intriguing to her from an early point, Selloni said: “Because these interfaces are natural, they’re in the natural world. You are entering into contact with surfaces just by leaning on that table. That’s where we are, that’s where our contact is. And so it is very dynamic. At the microscopic level, there are so many things happening that we don’t realize, so it’s a very rich area for research.”

Colleagues near and far

Current and former colleagues praised Selloni’s research and her approach to science at the Symposium and elsewhere.

“It’s a great honor to be congratulating Annabella on an amazing career,” said Sharon Hammes-Schiffer, the A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Chemistry at Princeton. “I’m representing the theorists at Princeton, but I’ve known her for many years. In the past, every time I listened to Annabella give a talk, I knew I was going to learn something useful and something new. It’s been wonderful being a colleague from afar and now here at Princeton.

“Annabella has really been a role model for how to do science. The three adjectives that come to mind when I think about her are integrity, rigor, and creativity. When she presents her work, it’s with an intellectual honesty that we don’t always see. She doesn’t sugarcoat, she doesn’t hype. She just gives it to you as it is. There is a careful approach to her science; each paper is a thoughtful presentation of a project, and again that’s very admirable. As for creativity, she was really ahead of her time in bringing the atomistic first principles for surface science. She has been pushing those boundaries all along.”

A few of Selloni's former group members and friends hung around to chat in Taylor Auditorium after the final Symposium presentation.

Professor of Chemistry Andrew Bocarsly mentioned the long academic friendship he has enjoyed with both Selloni and Roberto Car, Selloni’s husband of 38 years. Bocarsly shared an anecdote about the first class he and Selloni taught together in the late 1990s, a graduate course in solid state chemistry. Bocarsly said he had originally planned to come only to Selloni’s first lecture, joining the class later in the semester for his own teaching role.

“But she gave this fantastic lecture the very first time,” said Bocarsly. “I ended up staying for all the lectures she gave that term. That was eye opening for me. They were great lectures, and I think I learned more in that class than anybody.”

Michele Parrinello, now at the Italian Institute of Technology, is a long-time academic collaborator and friend. He said he attended the two-day Symposium because Selloni “deserves” the recognition.

“Yes, she’s a star in her field. A first-class scientist,” said Parrinello, who first met Selloni in the 1970s in Rome when she was studying under the Italian physicist Erio Tosatti.

“Of course it’s a long career so it is difficult to summarize in a few words what she did,” Parrinello said. “Annabella has worked the most on the application side and she did it in a very deep and profound way, discovering a new physical phenomena which has been demonstrated to be true by experimentalists. And also, she has been a mentor to so many people, so in that role she has been enormously important, too. Life has taken us to different continents, but we have always been very close.

“This was a great symposium, both on the scientific side but also on the human side,” Parrinello added. “People have received a lot from Annabella, and they have demonstrated their appreciation for that. She deserves that, because she really gives from the human side to the students and the collaborators.”

Salvatore Torquato, the Lewis Bernard Professor of Natural Sciences Professor of Chemistry, said he also values his long association with Selloni. “Annabella is a world-class leader in the application of density functional theory to fundamentally understand the physics and chemistry of surfaces, water and complex materials,” he said.

“A testament to the power of her computational skills is the validation of her seminal results by experiments. Annabella is a truly genuine, kind, and forthright person with a great sense of humor. She has been a wonderful friend over the years. The chemistry department has been extremely fortunate to have her as part of our faculty.”

Yosuke Kanai *06 was Selloni’s first Ph.D. student, and was supervised jointly by Selloni and Car. “Annabella and Roberto had very different styles of mentoring, at least when I was at Princeton. While Roberto has more of the ‘watch and learn’ style, Annabella would take you through logical thought processes step by step. It was an apprenticeship for becoming an independent-thinking scientist.

“I always appreciated how Annabella could pinpoint the key questions through which one would unravel and yield the essential understanding of very complicated phenomena.

“Also, when you talk to the alumni from Annabella’s group, they often talk about how working with her had a profound impact scientifically and personally. She genuinely cares, and that really impacts how she interacts with you as a person. I worked with many great scientists, but I have learned the most from Annabella in terms of how I mentor my own group members.” Today, Kanai is at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Selloni’s first physics adviser at the University of Rome, the Italian theoretical physicist Erio Tosatti, sent a recorded message for the Symposium: “You’ve done a lot of beautiful stuff, nice work, and I’m very proud of you. We are all proud of you.”

And Car, who introduced the event with some personal notes, ended with a presentation slide that said: “Thanks Annabella for all these years together. Let retirement be the beginning of a new adventure in life and science.”

A young scientist in Europe

Selloni was born in Sardinia, Italy on Sept. 28, 1951. Her family moved often from the time she was five years old, living at one point in her mother’s childhood town on the Adriatic Sea before finally settling in Rome where she spent her formative years. She is the daughter of an engineer and a homemaker and the middle child of three, each of them having, according to Selloni, “their own peculiarities.”

Selloni’s peculiarity was an aptitude for math, evident from a very young age. By the time she graduated from high school in Rome, she was fascinated by the deep fundamental questions of physics.

“It was always so clear to me what I wanted to do,” she said. “I’m surprised at myself because I’m very doubtful for many things. But it was so clear that I wanted to stay in research from a very young age. I had no doubt. It was automatic. I went straight to it.”

She attended La Sapienza University of Rome for her undergraduate degree, and recalls it as an intense time of both intellectual and political awakening: buildings at the University were often the site of protests and occupations. She graduated with a degree in physics in 1974. Selloni went on to do her Ph.D. at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Lausanne in Switzerland, working in solid state physics. She received her doctorate in 1979. There, she met Car, her husband-to-be.

Postdoctoral work followed at IBM’s Thomas J. Watson Research Center in upstate New York, a post she recalls with great fondness.

Selloni asking a pointed question during a Princeton Chemistry Department Retreat in 2015.

Selloni returned to La Sapienza as an assistant professor in 1982, working in the incipient field of scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). Back then researchers were simply trying to understand the images they were seeing, and these questions formed the bulk of her work at La Sapienza: what are the images representing, what are the traces, what is the geometry of the atoms that are being probed? In 1985, she published a paper on voltage-dependent STM that discussed the possible application of STM to surface electronic spectroscopy.

Following her three-year stint at La Sapienza in Rome, Selloni moved to Trieste, Italy to work at SISSA, the International School for Advanced Studies, where she was eventually made associate professor. Two years later, she published a paper on the structure and dynamics of electrons in molten salts, which she describes as her first foray into time-dependent molecular dynamics.

Selloni and Car (today the Ralph W. Dornte Professor in Chemistry at Princeton) were married in 1987. They welcomed their daughter, Martina, in 1988.

In the 1990s Selloni worked at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, where she received an invitation from Michael Gratzel, a physicist working on dye-sensitized solar cells in Lausanne, to do research on titanium dioxide (TiO2), the material used for Gratzel’s cells. This started a line of research that would be transformational to Selloni’s career and that continues to drive her work today. The original project involved trying to understand TiO2’s surface interaction with water and other small molecules relevant to the operation of solar cells.

She came to the Princeton University Department of Chemistry in 1999 initially as a senior researcher and lecturer, and was made associate professor with tenure in 2002. Selloni was named the David B. Jones Professor of Chemistry in 2008.

By this point, Selloni was already considered an expert on TiO2 anatase, the TiO2 polymorph most relevant in photocatalysis and solar energy conversion. She began investigating material defects, which had considerable influence on the material properties, and doping, to improve material efficacy in energy-related applications. Oxide materials have oxygen vacancies, which means they lose oxygen easily, especially if heated or if they undergo some treatment. An important part of her research contributed to understanding how these defects impacted performance.

At Princeton, the Selloni Group focused on the theory and modeling of oxide-water interfaces of relevance in environmental applications, (photo-)catalysis and electrochemistry. Selloni published one of her favorite recent papers in 2016, “Facet-dependent trapping and dynamics of excess electrons at anatase TiO2 surfaces and aqueous interfaces,” with Sencer Selcuk, then a graduate student in her group.

Their research examined how excess electrons from intrinsic defects, dopants and photoexcitation play a key role in many of the properties of TiO2. Using first-principles molecular dynamics simulations, they investigated the states and dynamics of the excess electrons from different donors near the most common anatase surfaces and aqueous interfaces. They found that the behavior of excess electrons depended significantly on the exposed anatase surface and the character of the electron donor.

Honors over the years

Over the years, Selloni was a visiting professor at the Fritz-Haber Institut of the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft in Berlin, Germany in 2009, and at the Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy in 2017. She also served on the advisory boards of the DOE “Center for Hybrid Approaches in Solar Energy to Liquid Fuels” (CHASE) (2020-2024); and the EFRC, “Ensembles of Photosynthetic Nanoreactors” (2022-to the present).

Attendees at the Symposium listening to a scholarly talk.

Selloni’s recent honors include the Plenary Lecture and Invited Speaker Award at the Conference on Computational Physics (2024); Fellow of the European Academy of Sciences (2016); Fellow of the American Physical Society (2008); APS Outstanding Referee (2012); and Distinguished Visiting Professor, Shinshu University, Nagano, Japan (2016-2023). She has served on editorial advisory boards at ACS Catalysis (2019-2024); and Surface Science (2019 to the present). She performed scientific community service through the APS DCOMP as chair of the executive committee (2022-2023).

She is predictably low-key about her next steps. Traveling back and forth between the United States and a second home in Milan, Italy. Visiting her daughter in Arizona. Reading. Movies. Contemplating getting another dog. She hopes to see more “live” music – Mozart and Bach at Carnegie Hall, and happily recalls seeing the Rolling Stones in Rome years ago: “Oh yes, I am full of admiration for them.”

Ultimately, Selloni looks forward to carrying on with the work she feels she has not yet completed.

“This is a turning point, yes. It’s been a good career. Most of the time I did what I wanted to do and what I liked to do. So I’ve been lucky and that has been wonderful. But I hope to continue doing the research,” said Selloni. “I still have a number of ideas that I would like to pursue, a few things I would like to do.”

Asked what subject in particular she intends to continue with, Selloni said: “It looks like I am always doing TiO2, , but that is really just an excuse. I’m doing many things. I’m still learning quite a bit, and so I’m happy about that.”