Giacinto Scoles, pioneer in the study of intermolecular forces, dies at 89

The Department of Chemistry mourns the passing of Giacinto Scoles, esteemed physical chemist and professor emeritus in the Department of Chemistry and the Donner Professor of Science, Emeritus, who died in Sassenheim, the Netherlands on Sept. 25 with his wife of nearly 60 years at his side. He was 89.

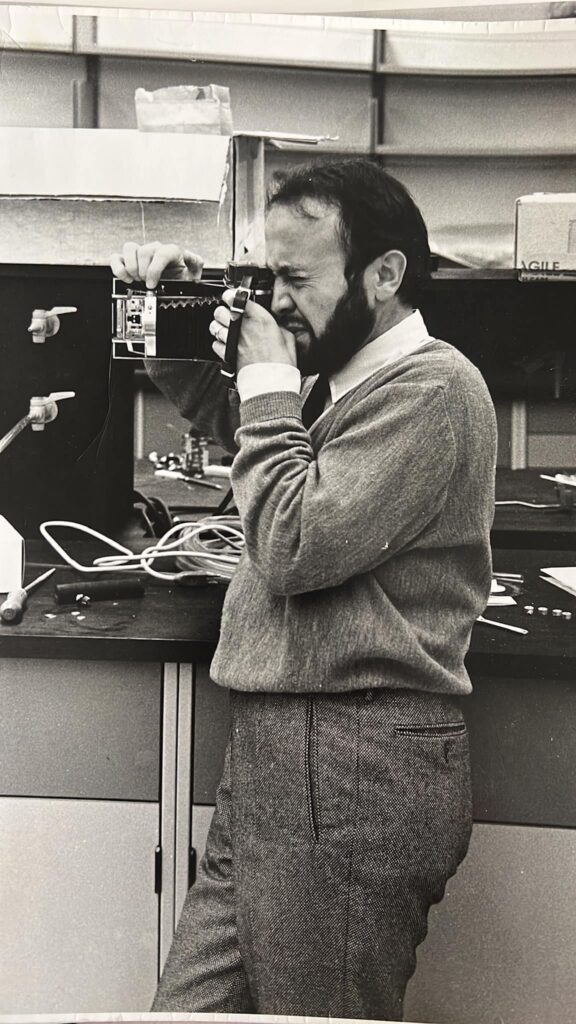

Throughout his career, Scoles straddled the fields of chemistry and physics, a charismatic and influential force in both. He made pioneering contributions to the study of intermolecular forces, molecule-surface interactions, and surface monolayers. His broad knowledge of molecular beam technology led to his role in the conception and development of an innovative machine called the cryogenic bolometer, a universal detector of atomic and molecular beams that Scoles later used to detect the kinetic and internal energy of molecular beams.

Described by colleagues as both a generous and a demanding scholar, Scoles was also known as “an excellent role model for what any scientist should try to become,” according to a special 2007 tribute published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry A. Known for his intellectual vigor, he was also as likely to carry out classical scattering experiments on the billiards table at his home.

Photo courtesy of Gigi Scoles

Scoles’ scholarly career spanned six decades across four countries, including Italy, Canada, the United States, and the Netherlands.

“I knew him before he came to Princeton, when he was in Italy. He was a great colleague and friend and was instrumental in bringing me to Princeton,” said Roberto Car, the Ralph W. *31 Dornte Professor in Chemistry. “He was a great experimentalist and a pioneer of molecular beam techniques, and he made some very important progress in a technique with clusters of helium at very, very low temperatures.”

In fact, Scoles was awarded the prestigious Franklin Medal in Physics in 2006 with J. Peter Toennies for his discovery of techniques for studying atoms and molecules by embedding them in tiny, ultra-cold droplets of helium. This work also led to a better understanding of the properties of superfluid helium.

“He was a great person,” Car added. “He had a very strong character and when he thought something was wrong, he was really adamant. He was an excellent colleague and a very important person to me.”

Annabella Selloni, the David B. Jones Professor of Chemistry, was advised by Scoles as she began her career at Princeton Chemistry. One of the things she admired most about him was that he “always said what he really thought.”

“He was positive and helpful, almost fatherly I would say. He introduced me to the concept of weak intermolecular interactions, which, having been trained as a solid-state physicist, I never thought to be interesting before,” Selloni said.

“My research with him focused on the structure of self-assembled molecular overlayers (SAMs) on metal surfaces, primarily on gold. Giacinto did the experimental work and had a deep understanding of the physical systems; I did the calculations and tried to learn from him.”

Gigi Scoles, his daughter, recounted one anecdote in particular: “My father enjoyed sparking everyone’s enthusiasm for science and took every opportunity to do so. A visit to my science class at the John Witherspoon Middle School [in Princeton] was no exception,” she said. “During that visit, he dipped a red rose into a thermos of liquid nitrogen and then tapped it on the desk at the front of the classroom, shattering it into little pieces that scattered in every direction. My classmate, Bebe Telfair (née Elisabeth Schmierer) would recall that event as a ‘core memory’ some 35 years later, so it seems he succeeded in exciting young minds about science.”

Long-time Colleagues and Friends

Kevin Lehmann was an assistant professor of chemistry at Princeton when he first met Scoles in 1987 and called him “… a very close personal friend, one of the closest in my entire life.” Lehmann and Scoles published 56 joint papers over a period of nearly 20 years.

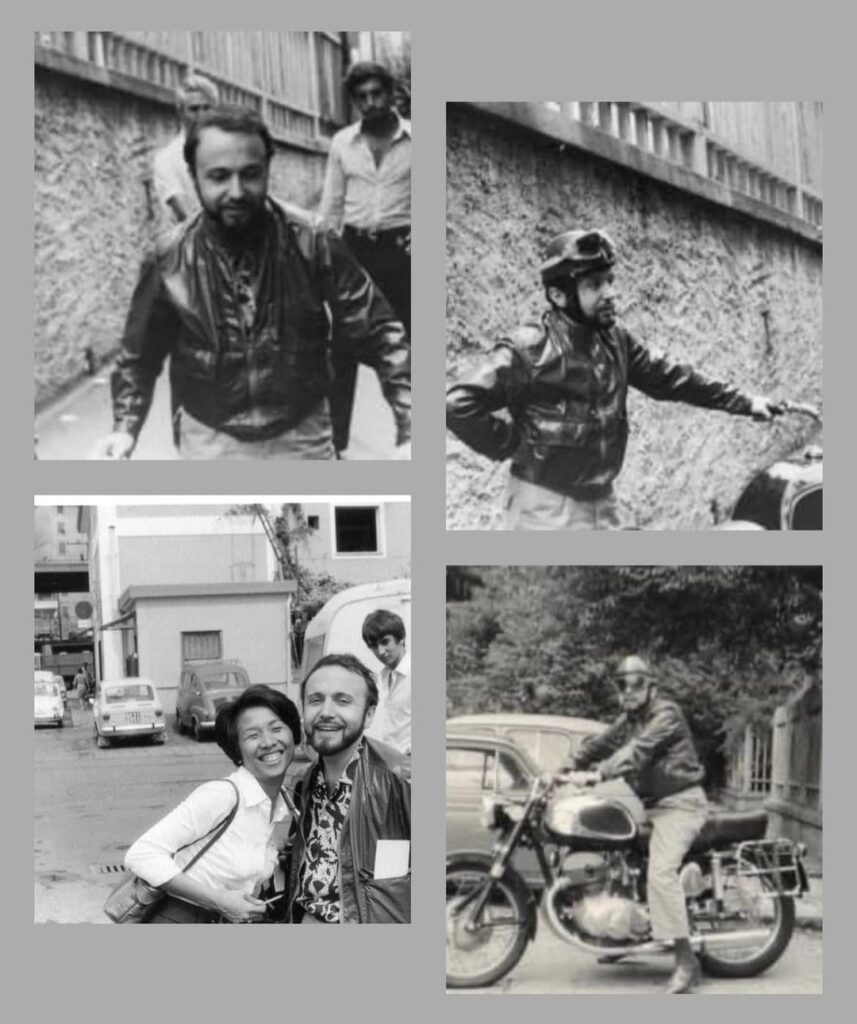

Montage courtesy of Gigi Scoles.

“Having worked with him meant a lifelong relationship, well beyond the submission of a thesis or the move to a different job or university. He held himself and others to the highest intellectual and ethical standards yet had deep empathy for others. He always demanded excellence from his students, but all recognized that he deeply cared for them, not only as scientists, but also as individuals,” Lehmann and five of Scoles’ former students wrote in a letter to colleagues after his death.

Lehmann later added via email: “Giacinto had the creativity to find important problems that he could make significant progress on. He was always a leader in opening new scientific areas and never one to jump on something because it was popular or because it was well-funded. I learned by studying his career that choice of problems is far more important in making an important scientific impact than other skills, such as the mathematical and analytical skills that are my own strengths.”

Salvatore Torquato, the Lewis Bernard Professor of Natural Sciences in the Department of Chemistry and the Department of Physics, said: “Giacinto was a superb scientist and an even better human being. A smile forms on my face recalling the inimitable passion and excited gesticulations he brought to any scientific discussion.

“He was a force of nature and will be greatly missed by his family, friends and colleagues.”

Born in Torino, Italy on April 2, 1935, Scoles was the son of a mechanical engineer who worked for the carmaker Fiat. He spent his early childhood in a village near Vicenza, northwest of Venice. After WWII and the death of his mother, his family moved to Barcelona, Spain. He returned to Italy for his university education at the University of Genoa where, after two years studying engineering, he switched to chemistry, earning his degree in 1959. He began his academic career there. After several additional academic roles, he became a professor of chemistry and physics at the University of Waterloo in Ontario in 1970.

Scoles started his Princeton career in 1987 as the Donner Professor of Science, where he pioneered the use of superfluid helium nanodroplets as the least-perturbing spectroscopy matrix for studying molecules and clusters. Together with Lehmann, now a professor at the University of Virginia, he used molecular beam technology in combination with Lehmann’s knowledge of spectroscopy to advance our understanding of intramolecular vibrational energy redistribution as well as the predissociation of van der Waals clusters, greatly increasing our knowledge of intermolecular forces and chemical reaction dynamics.

He organized and spearheaded the establishment of the experimental physics laboratory at the University of Trento in Italy; he was a cofounder of the Guelph-Waterloo Center for Graduate Work in Chemistry; and he played a leading role in establishing the Princeton Materials Institute upon his appointment at Princeton.

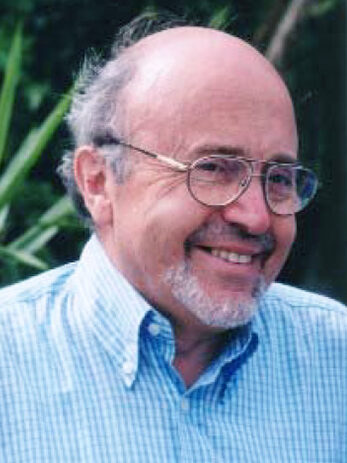

Photo courtesy of the Department of Chemistry

Among his awards and accolades, Scoles was elected Fellow to The Royal Society of the United Kingdom in 1997; he was an elected foreign member of the Royal Academy of Arts and Sciences of the Netherlands; he held two honorary doctorates (one in physics and one in science); and he was awarded the 2002 Peter Debye Award in Physical Chemistry and the 2003 Earle K. Plyler Prize in Molecular Spectroscopy.

He was the recipient of a European Research Council grant, and was at one time a lead organizer of nanotechnology conferences in Africa; these were “summer schools” that students could attend more easily, only having to travel within the continent. “Those were important parts of what he did and what he believed in – access to education for all, especially for women and people from developing countries,” said his daughter.

Scoles became emeritus in July of 2008, after which he held a professorship at the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, Italy, in conjunction with the Elettra Synchrotron Laboratories.

Due to declining health, he moved to the Netherlands in May of 2023 to be closer to his wife’s family.

Scoles is survived by Giok Lan Scoles, his wife of nearly 60 years; and their daughter, Gigi Mei Lan Scoles, who is currently serving overseas at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City, Mexico. The family asks that contributions in his memory be made to an organization devoted to finding a cure to Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, (PSP): CurePSP, at 325 Hudson Street, Floor 4, New York, NY 10013.

“I can think of no better way to honor my dad’s memory than to further scientific research on the disease that slowly made his body betray his brilliant scientific mind,” said Gigi Scoles.