Optimizing Your Graduate School Experience

Graduate school can be many things, at times stressful but rewarding or tedious then exciting. Though each experience is unique, most grad school problems are not. To help you find your rhythm as a researcher, three Princeton chemistry graduate alumni share strategies they developed (or wished they had) to successfully navigate the path to a PhD.

Graduate alumni:

Allison Doerr, PhD ‘05 – Senior editor at Nature Methods. Graduate advisor: George McLendon

Scott Semproni, PhD ’14 – Etch process engineer at Intel. Graduate advisor: Paul Chirik

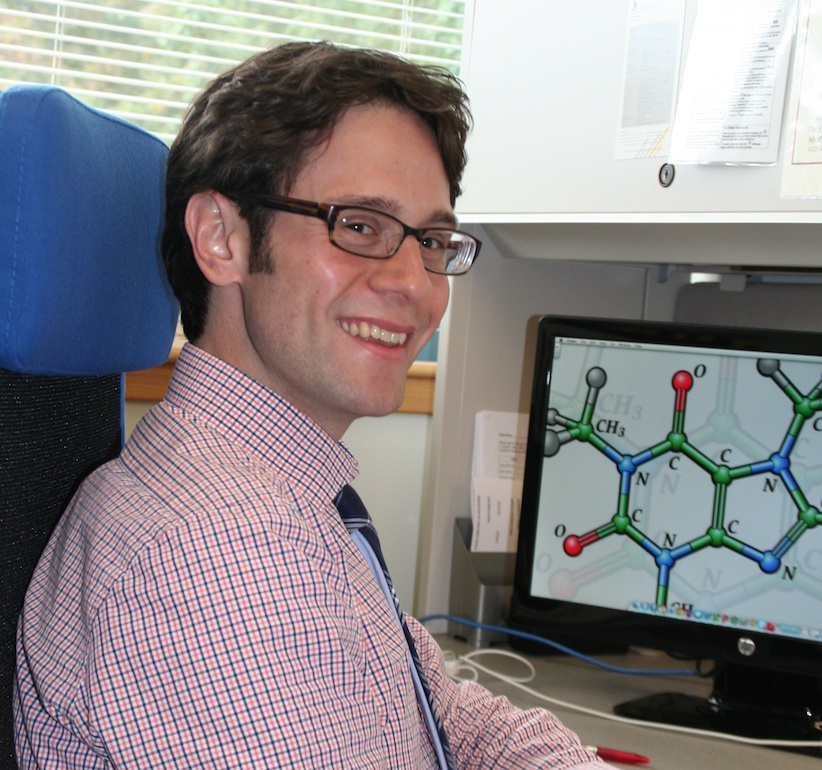

Thomas Umile, PhD ’12 – Assistant professor of chemistry at Gwynedd Mercy University. Graduate advisor: John T. Groves

1) With competing demands on your time throughout graduate school, what multi-tasking strategies helped you stay on top of everything?

Semproni: There are a lot of times in grad school when you set up an experiment and then have to wait before you can move on to the next step—even if it’s 10 or 15 minutes to bring something into the glove box. If you go back to your desk, the temptation to surf the internet can sometimes be almost overpowering. I always found that if I used those small moments to browse for papers, work up some data or read an article, it would be a big help with keeping things under control. Another key thing was analyzing, organizing and working up data as I collected it. It made writing papers and my thesis much, much less painful when the experimental data was already prepared.

Umile: A tactic I developed in graduate school—and use to this day—is to keep a running “to do” list on my desk of all the day-to-day things that need to be accomplished. Everything goes on the list, from planned experiments and lab group duties to personal things like scheduling doctor’s appointments or making sure to call home. (During one particularly busy time late in my grad school career, I even remember putting things like “remember to eat lunch” on my list!) It kept me productive and helped me make efficient use of my time.

Doerr: I agree wholeheartedly with Scott and Thomas—I am also a big fan of to-do lists, and love the feeling of crossing a task of the list! I think that working as a researcher was initially hard for me because I am a person who is motivated by deadlines and finishing tasks. In grad school I would try to map out a schedule of what I needed to accomplish each day, for example, if I knew there was a seminar I wanted to attend at 4pm, then I needed to start my NMR experiment at 2pm to make sure that I would be done in time. Setting a time schedule helped me to stay on task instead of letting days stretch endlessly to the wee hours of the night. I was the kind of student who liked to work relatively normal work hours, 10am to 6 or 7pm, which for the most part is totally doable, as long as you are organized and smart about utilizing experimental downtime to do other work-related tasks.

2) How did you stay motivated during those inevitable times when nothing seemed to be working?

Umile: When things weren’t working, I sometimes took that as a sign that it was time to step away from the bench, and I mean this in two different ways. For one, sometimes things aren’t working because you’re too stressed out and too focused, and a long walk up to Nassau Street for coffee can clear your head. However, sometimes “nothing working” means you’re thinking about your project in the wrong way. In short, the experiments are designed to fail because of how you’re going about it. If that’s the case, stepping away from the bench to look back over the literature or an old proposal you wrote, talk to your advisor, or brainstorm with friends in and out of the lab group can be really helpful. Perhaps it’s a sign to take the project in another direction, and learning when it’s time to do that is one of the major lessons of graduate school. In my experience, those “nothing is working” moments were usually the precursor to sudden periods of huge successes and great productivity. “Eureka moments” can and do happen!

Doerr: At times like that I always found that it was helpful to talk to my adviser. I picked him as an adviser in part because he seemed like he would be very supportive and would give good advice; and indeed he always seemed to know when something was worth pursuing in a different way or when something was just not working and it was time to step away. I think everyone in grad school needs a mentor—whether that is an adviser or an experienced postdoc—someone who has gone through the ropes before you and who can provide that encouragement. I think it’s therefore so important to pick a lab that not just does interesting work, but also provides a supportive environment.

Semproni: Also, some great advice I got from my PhD advisor was to never talk myself out of an experiment. A lot of the time it was the unexpected result or hare-brained idea that ended up paying off in the end and breaking me out of a rut.

Doerr: Maintaining a happy life outside of the lab was also a great source of motivation and stress relief. It could be going out for lunch with labmates, getting together regularly with friends, starting a relationship (in fact I met my husband at Princeton), participating in fun activities (for me, that was singing in the Chapel Choir and hosting dinner parties for friends), and just generally taking advantage of all the great things Princeton had to offer, as well as exploring the surrounding area, including NYC and Philadelphia.

3) When did you start planning for the next step after Princeton, and what resources did you find most helpful for finding your way?

Semproni: I started mulling over what I wanted to do before the summer of my final year at Princeton. I had thought about it for a long time but I think what I wanted to do really only started crystallizing in that final 18 months or so. I initially wanted to go into academia when I began grad school but ended up in industry. That choice slowly evolved over my graduate career. The career center at Princeton was actually very helpful for resume/CV preparation. They also will keep you informed of recruiting events that come to campus. The chemistry department does a great job of hosting outside recruiters and keeping people informed of who is coming to campus. It’s also good to keep an eye on other departments. I ended up attending recruiting sessions for companies that were run through the engineering and physics departments. I had a lot of friends from other groups in grad school that had gone on to varied careers in industry, post-docs and non-science jobs. Getting in touch with them was probably the most helpful.

Doerr: I was thinking about it from my very first year at Princeton. Originally I had wanted to be a professor at a small liberal arts college so I asked my adviser if I could teach a precept to gain teaching experience. Later on I realized that I was more interested in writing than teaching, so I started thinking about how I could pursue this as a career. I took a science writing seminar offered to chemistry grad students (which I would recommend to anyone, as writing is such a crucial part of communicating your research). I wrote a Review article with my adviser. And I used the money from my third year seminar winnings to attend a science writing workshop in Santa Fe, where I made great connections and learned about what science writers actually do. That ultimately led me to find an editorial internship at Nature Methods, where I am now a Senior Editor today. Networking is definitely important; take any opportunities that come your way, whether it is going to career forums at conferences, talking to seminar speakers one-on-one, or keeping in touch with colleagues who have left the lab for new ventures.

I think it’s very important to be passionate about your career. When I realized that I wasn’t passionate about research, I began looking into other careers where I could still use my PhD training. I think that there is a lot of pressure in grad school to go the route of postdoc and then academic research career, but it’s not for everyone. There are lots of different types of careers that someone with a PhD in chemistry is qualified to do, so it’s definitely worth exploring other options if you’re not laser-focused on becoming an academic researcher.

Credit: Donna Smyri

Umile: I had a sense early on that I wanted to work at a primarily undergraduate institution. My advisor was gracious enough to let me pursue some extra teaching assignments beyond the minimum required by the program so that I could get more experience in the classroom. The Teaching Transcript pedagogy development program run by the McGraw Center definitely helped prepare me to speak intelligently about teaching in cover letters and on interviews, and from what I hear it’s a pretty unique opportunity. Working with undergraduate researchers was also a great opportunity for someone pursing this type of career.

4) If you could go back in time, what advice would you give to yourself as a first-year student?

Doerr: I had a hard time finding a lab that was a good fit for me. I initially joined a lab where I thought the work would be really interesting, but I felt lost in what was really a “sink or swim” situation. I then made the tough decision to switch labs at the beginning of my second year, to a much more supportive lab, and was just so much happier. So I would say that it’s crucial not only to consider whose research seems most interesting, but whether you’ll be able to work well with your advisor and the other people in the lab, because this will be your life for the next 4 or so years! Take the initiative to talk to the other students in the lab, find out what lab life is really like and what the adviser is like.

Semproni: Grad school is a marathon, not a sprint. It’s helpful to remember that when are stuck in the doldrums on a project and nothing seems to be going right. Also, always have something to look forward to, even if it’s just beers on Friday.

Umile: There are three things I wish I could tell “first year me.” First and most importantly, have confidence in your ideas. Looking back as I wrote my dissertation, I recognized that many of the ideas I “threw out” or never pursued weren’t as amateurish as I thought, and I wish I followed up on them. Second, network as much as possible! Make friends outside your normal circle at social, meet grad students from other departments, and sign up for as many lunches with seminar speakers as you can. You never know who will be your next colleague, collaborator, postdoc advisor, or boss. Finally, keep a better notebook! Every detail may matter someday, and you don’t want to have to redo experiments later on to re-learn some detail you didn’t write down.

5) What are some of your favorite graduate school memories from Princeton?

Semproni: Frickmas was fantastic and the skits were always a lot of fun. I also really enjoyed the summer barbecue. My 3rd year at Princeton the first years roasted a whole pig. It was amazing.

Doerr: Every year we had a Halloween party in old Frick, which had a spooky Gothic foyer, perfect for the occasion. People would dress up for a best-costume contest. Frickmas was also always lots of fun; when it was my year’s turn for the skit we put on a kind of soap opera-type show about who else: Princeton chemistry professors! I had one friend who was a brilliant at impressions, and he just cracked everyone up.

Umile: I really miss the department socials every Friday evening, usually held right after seminar. They were a great way to celebrate the end of another week with friends, especially in the summer when we had them outside. It was nice to always have a “standing plan” on Friday evenings, and it was a great opportunity to mingle with fellow graduate students who weren’t in your regular social circle.