Postdoc Q&A: Nicholas D. Chiappini

As a boy growing up in Vernon, New Jersey, Nick Chiappini was all about outer space. Then, he took an eighth-grade chemistry class with Carol Lepse at Glen Meadow Middle School that changed everything. No one lesson in particular convinced him, but rather his teacher’s way of framing chemistry as a tool to understand the world. He was hooked. Today, following a Ph.D. in chemistry at Stanford University under Justin Du Bois, Chiappini is a postdoctoral researcher with the Knowles Group, happy to be back on the East Coast and pursuing the field that has been his passion since middle school. Below, some reflections on his experiences so far.

Photo courtesy of Nicholas D. Chiappini

AFTER YOUR Ph.D., HOW DID YOU DECIDE ON PRINCETON?

For my postdoc, I knew I wanted to gain experience in photocatalysis, and Princeton’s basically the leader in that regard. I was really interested in working in a department that had so much expertise in the field, let alone one in my beautiful home state of New Jersey. I want one day to have my own research group, and so I want to acquire all the skills I can in the short term that I’m here to be prepared for that.

EAST COAST OR WEST COAST?

Oh, I love New Jersey. I’m an unrepentant advocate of New Jersey. I love it so much. I enjoyed my time on the West Coast, but I think I just vibe a little bit more with the East Coast. Plus, you definitely can’t get a Taylor ham (or pork roll, since we’re in Central Jersey) egg-and-cheese sandwich on the West Coast.

WHY DID PROFESSOR ROB KNOWLES’ GROUP APPEAL TO YOU?

If you talk to anybody in the field and you bring up Rob’s name, the immediate response is that he’s a really kind and wonderful person in addition to being unquestionably brilliant. He is a titan when it comes to knowing things, but he also has the emotional intelligence to sense when something is wrong and he can act on that and provide that guidance. When I visited in August of 2018, I just really hit it off with the group. And that was absolutely something I wanted.

WHAT ARE YOU WORKING ON NOW?

The Knowles Group is really interested in this type of reactivity called proton-coupled electron transfer or “PCET.” Essentially, you can do oxidations or reductions that aren’t normally possible by pre-associating, say, the species you want to oxidize with a base in the presence of an oxidant. So, what I was particularly interested in when I first started was using a type of functional group called the tetrazole. They tend to be a pretty high-energy species. Like, explosive, almost. I was really drawn to them because they’re very distinct in their properties, kind of like a carboxylic acid, but with some distinguishing features. They have very, very strong nitrogen-hydrogen bonds, so if I could break that bond with PCET, it’d have a lot of driving force to do chemistry with the reforming bond that something with a weaker bond might not be able to do.

HOW ABOUT WHEN RESEARCH DOESN’T WORK OUT AS YOU ANTICIPATED?

Ideas can be great and they can look really good on paper, but there are a lot of times where you just need to do the experiment and be prepared to change course if it is a no-go. My subsequent projects are broadly related in that I’m trying to use Knowles photochemistry to do reactions that are energetically challenging. Things that are really, really uphill. In principle, that’s a unifying theme for a lot of the chemistry in our group.

WHAT IS THE MOST IMPORTANT SKILL TO A SCIENTIST?

I feel like flexibility is incredibly important. It’s very easy to get stuck in a rut for a long time in hopes of trying to get where you want to go. I’d say one of the most important skills I learned, at least with my Ph.D., was trying to identify when the stopping point is. When does the cost-benefit analysis pay off? Will investing another month in this maybe lead me to a result, or is it time to start looking at something else?

HOW DO YOU KNOW WHEN IT’S TIME TO PIVOT?

It’s really hard. I think the way I learned to be at peace with things not working out is not to look at it as time wasted, but as learning ways to not do something. Even if the results didn’t lend themselves to something I wanted to achieve, I still learned how to do the experiments that were required. It’s not a sunk cost. And if I’m approaching what I see as the end of a project, I’ll pursue things in parallel. That way, I can have some success or some room to play in while trying to make that difficult call.

YOU’VE SAID YOU LIKE MENTORING. HOW DO YOU KNOW WHEN YOU ARE READY TO TAKE ON THAT ROLE?

You’re always your own worst critic, and that’s something you have to go in knowing from the beginning. Whether or not you feel that your scientific accolades are enough to mentor somebody, your lived experiences are. They’re extremely valuable. You may not feel that you can guide someone scientifically yet, but everyone’s journey is unique, and everybody has something that they can learn from you.

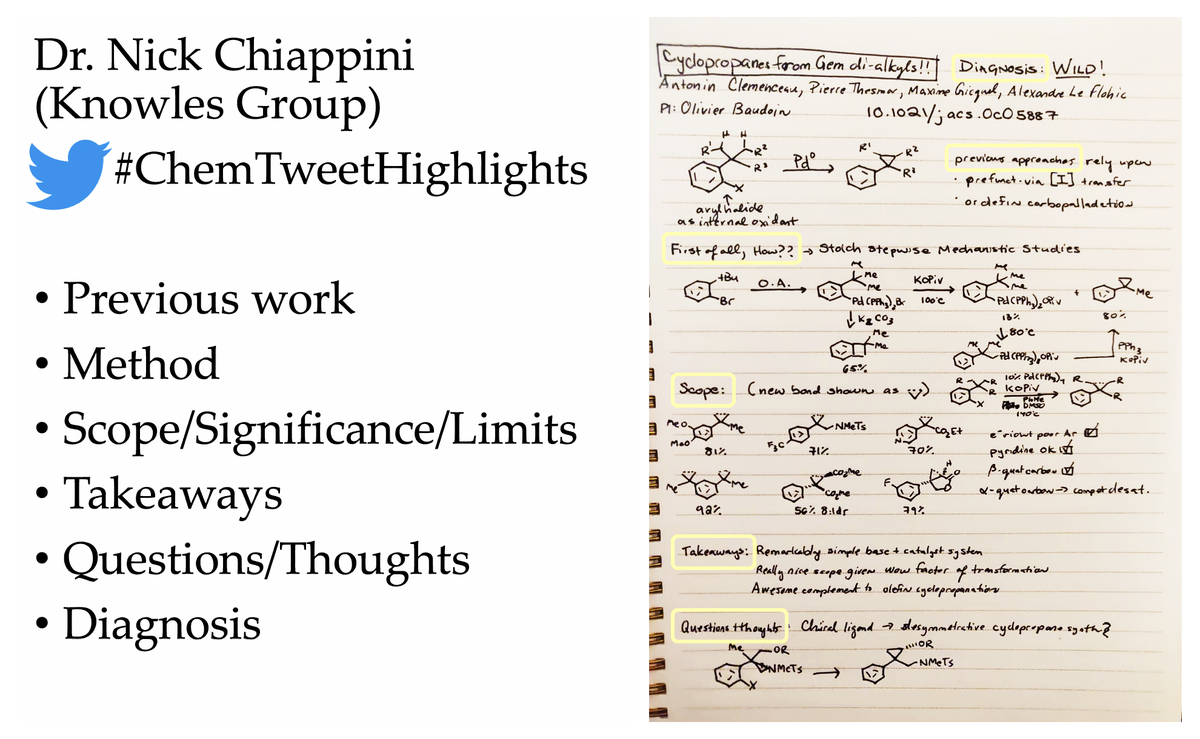

YOU HAVE A REPUTATION FOR CRAFTING METICULOUS NOTES…

Yes, that’s one of the ways I keep track of the literature. I just make summaries for myself. There are a lot of barriers to people being able to access science. With a lot of published stuff, there’s a paywall involved. Part of the reason I was so passionate about writing them up was, I did my undergrad at an institution that had access to a good number of journals, but not everything. I remember my frustration with that. So I wondered, how can I open up the science to people; can I give them CliffsNotes on a paper or something? Or, if someone doesn’t have time to take a deep dive into science, can they at least get an idea from my notes?

Photo courtesy of Dr. Sonja Francis

WHAT ARE YOUR PURSUITS OUTSIDE OF CHEMISTRY?

One of my biggest passions is media of all sorts, but particularly cartoons. I watch immense amounts of cartoons – retro, modern. One of the things that stuck out to me in the past 10 years or so is, as a gay man, to be able to see LGBT characters not only on adult cartoons but on kids’ cartoons has been so great. Cartoons are really effective ways to convey complex social issues. And I guess that’s sort of how I feel about science. I want my science to be accessible and I want my science to be something that people can digest. In that sense, animation and cartoons as an art form have always been a big inspiration for me.

WHAT ADVICE WOULD YOU GIVE ON HOW TO MAXIMIZE YOUR TIME AT PRINCETON?

My biggest piece of advice is, don’t try to work in isolation. As much as possible, try to meet people. If you operate within the bubble, you’ll gain a certain amount of experience, yes, but I feel like it can be so much richer if you are aware of what’s going on around you personally and professionally. Try to meet people. Try to branch out a little bit more.