Chemistry’s “flameworker” Mike Souza retires after 30 years

Michael Souza is retiring from his position as scientific glassblower at the Department of Chemistry after 30 years, effective this week.

With a clear view of how his field has shifted over the decades and an unshakeable belief in its essential contributions, Souza said we continue to live in the “Age of Glass,” driven by ongoing innovations in flameworking.

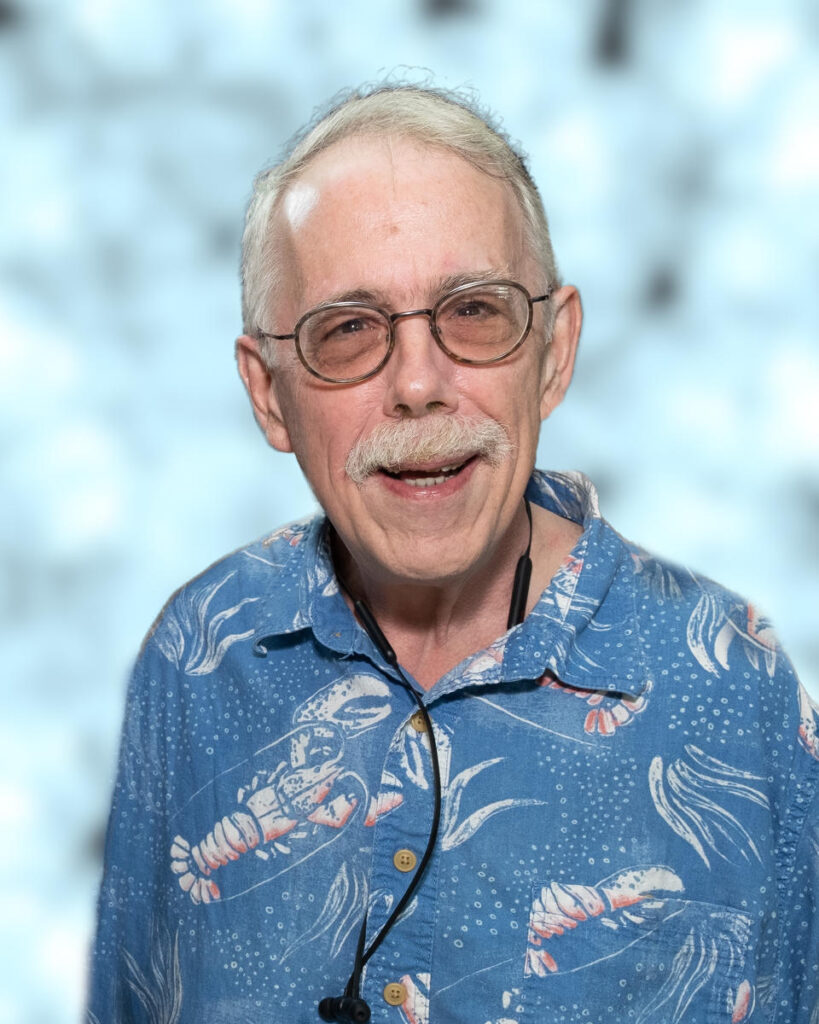

Michael Souza, scientific glassblower at the Department of Chemistry since 1992.

“Galileo’s scientific method changed everything from mythology to science, and he did it through a glass lens,” said Souza this month at his studio in Jadwin Hall. “If you took 20 of the most important scientific advances since then, at least 15 of them required glass as the major component.

“Newton’s Prism; it broke apart white light into the rainbow and recombined it back to white light. J.J Thompson’s electron tube. Robert Boyle’s Bell Jar, used for the basis of his gas laws and, later, for the discovery of photosynthesis. Lasers, too, were first made out of glass. They’re all advances based on scientific glassblowing vessels. You could just go on and on.”

Souza’s work has seen decades of commissions for research projects from Princeton University, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Stanford Linear Accelerator, the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility, the Smithsonian, the Department of Energy, the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, and the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, among many others.

Celebrated for his encyclopedic knowledge of the malleable properties of glass, Souza said he enjoys puzzling through the demands of a particular project. His most notable skill is an ability to work a rare and difficult type of glass known as aluminosilicate. Though it was most commonly used for halogen lighting, it remains an essential material in physics research because it is virtually impermeable to helium and its very rare isotope 3He.

Souza shaping a large-diameter glass for a project.

Ranging in his conversation and always eager to talk about what he does, Souza nevertheless challenges the idea that he practices an “art.” It’s something he has heard many times throughout his career and he would like, near the close of it, to put that theory to rest.

“If I have an art, it’s innovation. Because I’m dealing mostly with graduate students and researchers who don’t have any clue about glass, even maybe as a property, and what it can do,” said Souza. “Everybody’s experience with glass is breaking it. But it’s the most facile material we have available on this planet. It’s the most rigid material we know of, and the most pliable. And to work with fire and coax it along through those stages, it’s almost meditative. It’s magic.”

Signature Projects

Souza dropped out of high school to work full time, and did not finish his education until the age of 31. He also holds no advanced degrees. Instead, he learned his trade on the job, using curiosity and a growing appreciation of the medium to bolster his work.

It all started at a glassblowing factory in Evanston, Illinois, where his father was a production manager. Souza senior took his five sons to the factory on nights and weekends as “a way to keep track of us.” Together, the boys loaded furnaces and washed glass. It wasn’t until years later that he got a close view of what glassblowers actually do.

“When I saw them work the glass for the first time, it just captivated me,” he said.

When he arrived at Princeton Chemistry in 1992, there was an abundance of work just keeping the labs stocked with experiment-grade glass and distillation equipment. Advances in analytical and combinatorial technology, however, induced a shift to much smaller-scale chemistry, altering the amount of industrial glass needed almost overnight.

So Souza expanded his lab’s mission by seeking external commissions.

Some of his favorite projects over the years include the Muon Drift Chamber he made for the Department of Physics, shortly after arriving at Princeton, using aluminosilicate glass. “I felt like a child being tossed into the deep end of the pool to learn how to swim,” he said.

Souza and the team he assembled for the stellarator work at Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (l to r): Bob Russel from Salem Community College, Klaus Paris of Glassblower’s Shop LLC, and Michael Zarnstorff of PPPL.

He also worked on the world’s first jet-stirred reactor at supercritical pressures, designed to operate at 220 atms, roughly 3,000 psi, for Yiguang Ju in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering; and the world’s first Permanent Magnet Stellarator, a project for the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

On an even broader scale, a series of glass tubes created by Souza will be doing a flyby of a Jovian moon several years from now aboard NASA’s Europa spacecraft.

“The fact is that none of these accomplishments would have been possible without the support of Princeton Chemistry,” Souza said. “I’m eternally grateful to them.”

In addition, he took on numerous glassblowing interns from Salem Community College in Carney’s Point, NJ, the country’s only college degree program for scientific glassblowing. One of them, Kiva Ford, is today a glassblower at the University of Notre Dame.

“Mike Souza is a national treasure. His dedication and passion for scientific glassblowing is remarkable, and he is one of the best teachers I have ever had,” said Ford. “He is admired internationally for his incredible contributions to science, his broad knowledge of scientific glassblowing, and his skill in manipulation and mastery of the material. Scientific glassblowers look at his work in awe.”

Souza, who lives in East Windsor, has two grown sons. He and his wife, Mary, recently renewed their wedding vows after 37 years of marriage. Upon retirement, he plans to freelance his skills and will teach as a guest instructor at Salem Community College, the Corning Museum of Glass, Penland Craft Center, and Glass Roots, a glass arts studio in Newark, NJ.

Souza’s departs with an irreplaceable knowledge of his material and its properties, which he is willing to share with anyone who asks.

“Now bear in mind, every element you put in glass will change its properties somewhat – how it performs, whether it can take temperature, whether it has color or is clear,” Souza said. “But let’s say we take 10 elements commonly used for making glass, and we’re going to make a different product of glass every second.

“It would take you longer than the universe has existed to run through all the possibilities.”