Collaboration provides computational support for cryptochrome-based magnetoreception in birds

A tiny songbird traveling hundreds of miles at night to stick a very specific landing has to be one of nature’s most impressive feats. We have understood for decades that migratory birds navigate using the Earth’s magnetic field, and for years that a receptor protein in the avian eye is likely responsible for that ability.

What we didn’t understand are the mechanics of it all: how a light-sensitive protein complex called cryptochrome lets birds tap into the Earth’s weak magnetic field. Your average refrigerator magnet has a stronger pull than the field of the entire planet, so how are birds able to access it?

Now, NIH-funded research published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS) by the Hammes-Schiffer Group and the Subotnik Group lays out the biophysics behind a radical-pair mechanism and its role in night migration.

This field of work has vast implications for sensing devices and imaging capabilities both biologically (humans have cryptochromes too), and technologically.

Jiate Luo, the paper's first author, laughs as he shows off a plastic robin given to him by his labmates on the publication of the research.

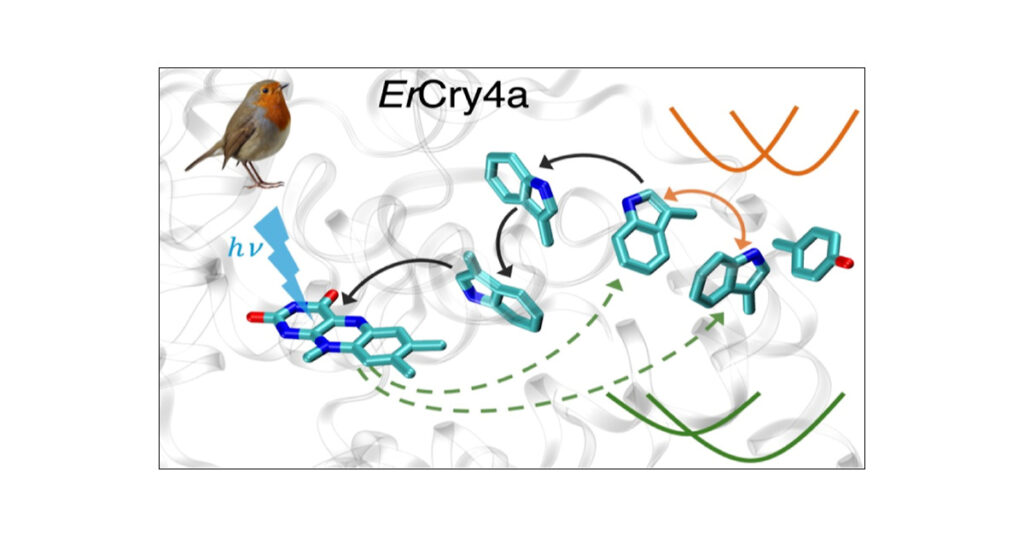

Researchers in the two labs used computational simulations to study a flavin in a bird’s retina known to generate magnetoreception through a specific cryptochrome called cryptochrome-4a. They identified the principal electron transfer pathway for this mechanism and the well-separated radical pairs essential to its dynamics.

Their theoretical research also proposed that amino acid residues in the protein environment play an important stabilization role by providing a longer lifespan to the sensing process.

“If we can understand how this magnetic field sensing works, then we could use cryptochromes as sensors in other contexts,” said Sharon Hammes-Schiffer, the A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Chemistry. “We also have cryptochromes in our bodies, and they are relevant to Circadian rhythms. Understanding this mechanism could have biomedical implications for humans, among many other applications.”

The groups’ paper, Protein and Solvent Reorganization Drives Radical Pair Stability in Avian Cryptochrome 4a, was published in collaboration with colleagues at Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg.

Well-separated radical pairs

Researchers demonstrate with this paper that a well-separated radical pair, or pairs of correlated electrons formed on separate molecules, is the exact magnetic sensor in migrating birds.

“Our goal with this research was to use theoretical and computational methods to figure out what is going on with these well-separated radical pairs: how they converse with each other, how they stabilize, and how they recombine,” said Jiate Luo, a postdoc in the Hammes-Schiffer Group and first author on the paper.

“This is what drove me to this field from my undergraduate work and my Ph.D.,” said Luo, “because you just cannot imagine that quantum mechanics has an impact on birds finding their breeding grounds in some part of North Africa from Europe, and how they ‘see’ the magnetic field when we humans cannot.

“And it’s not a simple question. It turns out it requires the efforts of physicists, chemists, and biologists to understand it.”

Using first-principles electronic structure methods and hybrid quantum mechanical simulations, the labs studied the stabilization, interconversion, and recombination of well-separated radical pairs that have been theorized since 2021 to be involved in magnetoreceptivity.

The flavin is photoexcited at a specific wavelength range inhabited by blue light, which triggers stepwise electron transfer: first to a “very close” tryptophan, a type of amino acid; then to a second tryptophan; and finally to a third and fourth, creating a series of radical pairs. The final radical pair occurs more than 18 angstroms away from the flavin. As the electron is sequentially transferred, the protein structure reorganizes around a charge as the radical pair forms, providing the essential stability and the optimal lifespan for magnetic sensing to take place.

“Since the Earth’s magnetic field is very weak, you have to give time for this molecule to sense that,” said Luo. “So your radical pair lifetime should be as long or longer than one microsecond. If they are too close, they will very quickly recombine. We’ve shown that the separation is more than 18 angstroms away. They should be well-separated because then they could be stable with a very long lifetime.

“We also found that the protein and solvent reorganization play a very important role in stabilizing these radical pairs to an optimal lifetime, as long as microseconds.”

The joint paper forms the basis for more collaborative work in the future.

“There’s this whole field of study called magnetic field effects in chemistry that nobody really understands,” said Joseph Subotnik, the David B. Jones Professor of Chemistry. “It’s a long-term project. Right now, we’re trying to figure out from the very beginning. We want to know, can we say something interesting about the dynamics of this protein? That’s where we’re headed.”

Protein and Solvent Reorganization Drives Radical Pair Stability in Avian Cryptochrome 4a was authored by Jiate Luo, Jonathan Hungerland, Ilia Solov’yov, Joseph Subotnik, and Sharon Hammes-Schiffer. It was published in JACS in November 2025. Research was supported with funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM139449.