MacMillan Nobel One Year In: “The medal’s the thing”

For David MacMillan, it all starts with the Nobel medal, the fulcrum around which the whole experience spins. It comes in its own blue velvet box. Inside, a perfect circle of 18-carat gold weighing 175 grams with one name engraved on the back.

The medal has a mesmerizing effect on everyone who sees it, from New York to Glasgow to Hong Kong. It makes some people giddy. It makes some people teary. It makes almost everyone who holds it high-five someone else.

MacMillan, winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, said the medal is where his year-long experience of being a laureate begins: not with the 5:30 a.m. phone call from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences last October or the ceremonies in his honor or the knighthood conferred on him in June. But with the medal itself.

“You can take the medal anywhere in the world and see the looks on people’s faces when you open the box and they get to hold it, and it’s just astounding,” said MacMillan, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of Chemistry. “It makes people so happy. It’s been such an incredible privilege to go around the world and hand this object around and have people just light up.

“It’s just such a human experience. And it’s so reproducible the world over. People have the exact same reaction whether you’re in Italy, Spain, Korea, or Scotland. It’s not really about me. The medal’s the thing.”

(And so far, it’s only been dropped twice. No dents yet.)

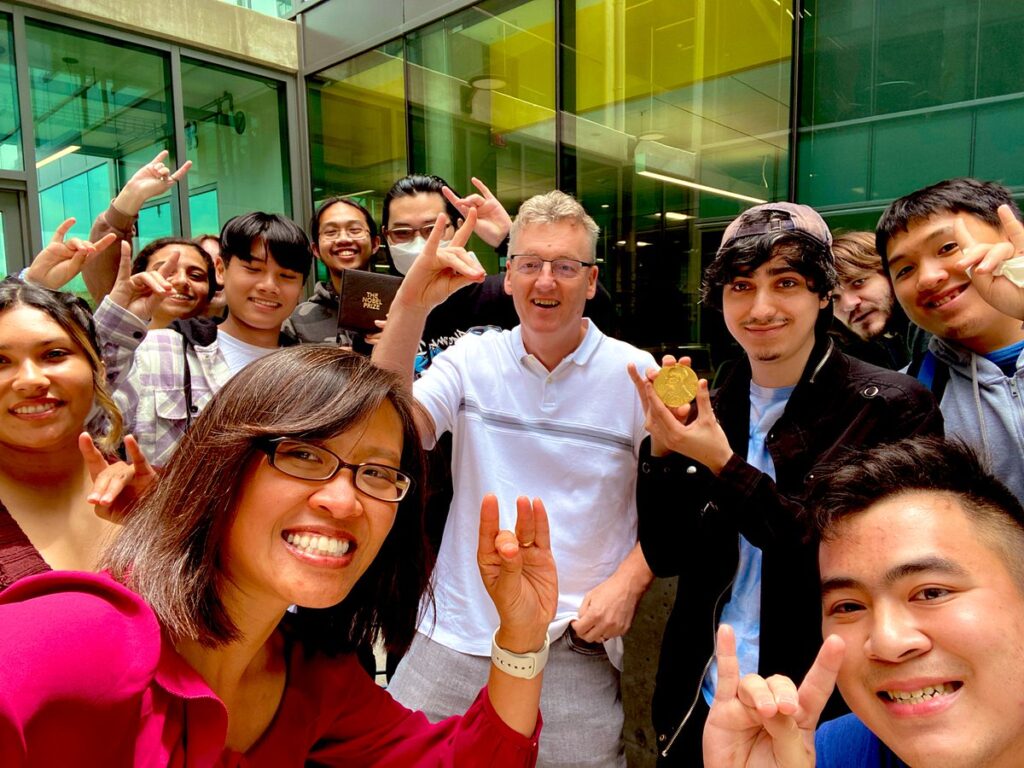

MacMillan visiting UC Irvine, surrounded by members of the VM Dong Group, with Vy Dong (foreground, left), a former MacMillan graduate student. They are making the sign of an anteater, the UC Irvine mascot.

What continues to surprise MacMillan 12 months after winning the Nobel for his development of asymmetric organocatalysis, jointly with Benjamin List of the Max Planck Institute, is the intensity of the experience, the unrelenting buzz that occasionally threatens equilibrium.

The past year has been a dizzying crush of events for the Department of Chemistry’s Nobel laureate and his family. And although three new chemistry laureates were named by the Nobel Prize Organization in Sweden last week, the pace for MacMillan continues.

A rough outline of highlights over the past year includes: returning to his alma mater, the University of Glasgow, for an honorary degree. Meeting William Shatner for a radio interview. Attending the inauguration of the new president of the Republic of Korea as a personal guest. Speaking to displaced Ukrainian students via Zoom for a one-hour lecture and answering their complex chemistry questions. Founding The May and Billy MacMillan Foundation, with its decidedly commonplace name, to honor his parents and underprivileged college-bound Scots.

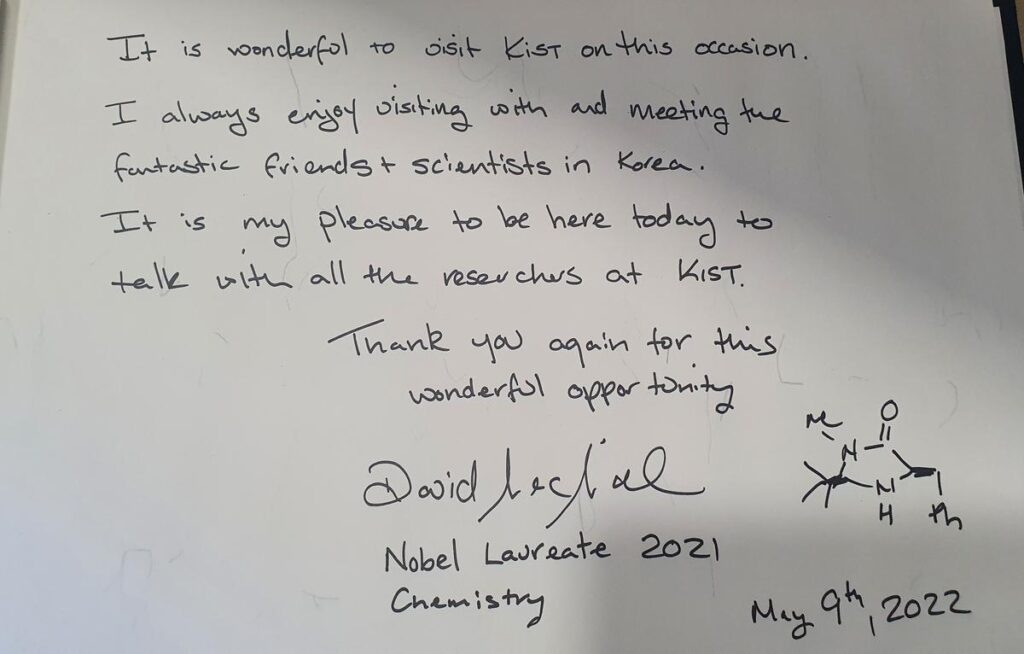

A note MacMillan left after his visit to the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST), thanking hosts and students who attended the lecture.

It continues with meeting the raucous hosts of the football (i.e. soccer) program, “Off the Ball,” of which he’s been a fan for 25 years. A quiet, candlelit dinner with his wife, Jean, at a Michelin-starred restaurant in Parma, Italy to escape the frantic pace. Trying to work on his golf game and finding little time for it. A Nobel plaque dedication at UC Berkeley with former students that had MacMillan so teary he could hardly see. An insider’s tour of the Glenfarclas Distillery in Ballindalloch, Scotland to dip a glass into its famous river of blended whiskeys. Walking onto the football field he worshipped as a boy and being greeted by football icons. Hanging out with Sir Alexander Ferguson, who managed Manchester United from 1986 to 2013, and hearing the inside bits of strategy and brinksmanship about legendary games.

A Call from the U.K.

And then, there was that phone call from the British Embassy.

“When I was in Korea, I got a phone call from the hotel saying, the British Embassy’s trying to reach you. You think something bad has happened,” said MacMillan. “And then suddenly someone tells you that it’s Buckingham Palace on the line and you’ve been knighted. And I just remember sitting on the edge of the bed with a bathrobe on and the tears just running down my face.

“The woman at the other end of the line, a dame of the British Empire, waited politely and then said, ‘You know you have to verbally accept it.’ But I didn’t answer her. I couldn’t speak because I was just so choked up. She was probably thinking, what is wrong with this guy?”

MacMillan with Professor of Chemistry Martin Semmelhack on the day the 2021 Nobel Prize was announced last year, on the Frick Lab patio with colleagues, students, and friends.

So much of the past year, MacMillan said, has to do with ceremony and celebrity rather than the science itself. That, of course, came much earlier. The development of asymmetric organocatalysis formally began in a laboratory at UC Berkeley back in the 1990s.

That is how the Nobel Prize works—it is historically awarded for groundbreaking technologies that have already stood the test of time.

In acknowledgement of both the passage of the years and those who have contributed to his achievements, MacMillan famously said during a press conference in Washington, D.C. last year: “I didn’t do much. It was my students who did everything.”

MacMillan’s least favorite question is, what kind of advice would you give to young scientists? There are too many ways to track to the top, he said. Everyone does it differently. So, to imagine there is one equation or pathway is to miss an important point.

“Anyone who is smart and driven can get there,” MacMillan said. “I’m sort of the surreal proof of that.”

The Nobel Medal, given out to chemistry laureates by the Royal Swedish Academy of Scientists.

Nonetheless, when he was at the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting in Germany this past June and had the opportunity to sit down with Randy Schekman, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2013, MacMillan drank in every word. What a seasoned laureate has to tell a newbie, it turns out, is a lot.

So, what counsel would MacMillan pass on to new laureates Carolyn Bertozzi, Morten Meldal, and K. Barry Sharpless, who were jointly awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry last week?

“The thing I would tell them is, enjoy it your way. There is no right way or wrong way to do this. Do the things that you’re excited about and that are worth it for you and your family,” said MacMillan.

“People may not get the science or the chemistry behind it, but they get the medal. They know what it means. And so what they really want is to talk to a real person. Just be yourself and you’ll have a great time with it.

“And make sure you bring your family along with you,” he added. “They will keep your feet on the ground.”