Remote Teaching: The View from Frick

The teaching video opens on the black void of space spangled with stars. Then, in a sequence that would make George Lucas proud, a message in gold letters scrolls up from the bottom of the screen to introduce a lab combining listening skills with an introduction to Excel. Including music. And poems. And stop-action LEGO dragons voiced with theatrical flair by Sonja Francis, lecturer in chemistry.

The video is just one in a package of instructional alternatives developed this Zoom-ester by the Department of Chemistry to meet the demands of online teaching. Deprived of traditional face-to-face interactions with students, Frick educators have responded with a commitment to remote teaching that – two semesters and 11 months into the pandemic – seems to be working just fine.

“I like the idea of backward design. I start with what I want the students to learn and design backwards from there,” said Francis. “It isn’t fair to ask students to use their own resources to buy things. So we purposely made the decision that the only materials they would need for these courses is the internet.

“The dragon video was a neat way to not only standardize the labs but to practice the kinds of calculations students should know coming into the course,” Francis added. “I think the students didn’t have high hopes for on-line labs at first. But after the dragons they said, ‘Oh, that was really cool. We’re excited to see what else you can do.’ ”

John Groves, who holds the Hugh Stott Taylor Chair of Chemistry, went through several iterations before he found the technology that best supported his advanced biochemistry course. His original plan was to use a Frick Lab meeting room and stream classes from there, but that would have necessitated a camera-person to capture the whole of each lecture. Now, he uses an iPad Pro to live-stream PowerPoint lectures from his home.

“I post these on Blackboard ahead of time and I record the lectures on Zoom in the event that someone misses a ‘live’ class. One student in the course is in Beijing, so there are time zone considerations as well,” said Groves. “Overall, it is still a learning process, but the students in the class have been most helpful.”

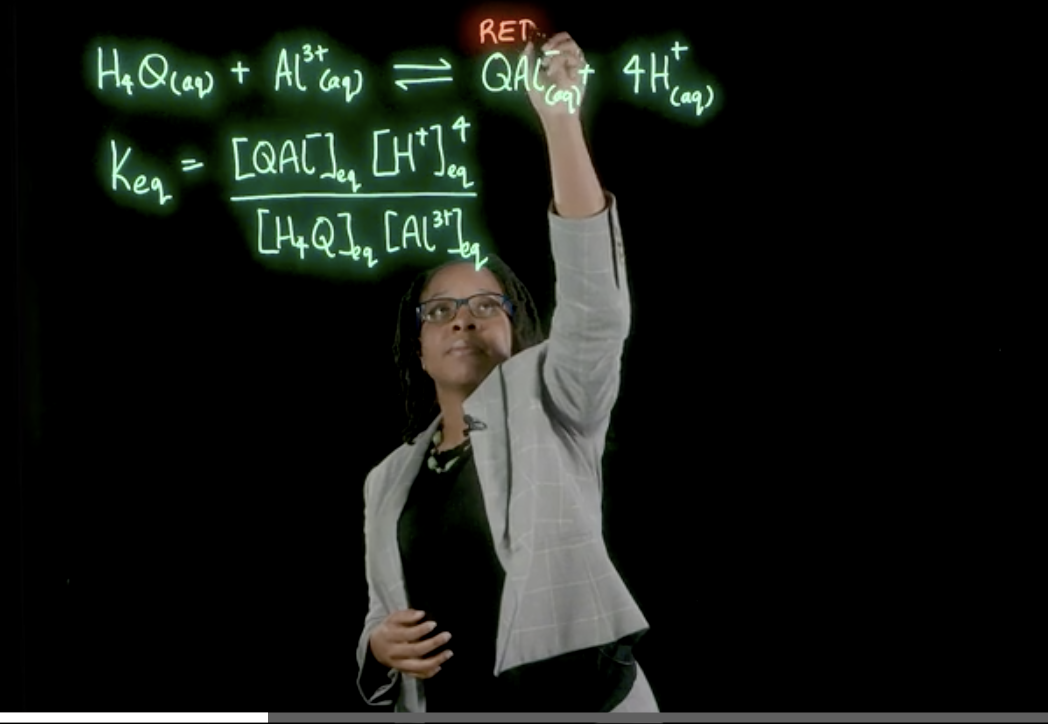

Groves added that he hopes to build his own lightboard – an on-line white board made of specialized glass that can be drawn on – for his CHM 544 course this spring.

EMPHASIS ON INTERACTION

Professor of Chemistry Michael Hecht wanted to salvage as much interaction as possible in the face of on-line teaching constraints. So in September, he asked students to come to the “live” CHM 201 Zoom sessions whenever possible (sessions are also taped to accommodate international students). On a typical day, attendance hovers at around 120, yielding a sea of close-up faces.

“One surprise is that the Zoom experience almost feels more familiar because we’re seeing each other’s faces very closely,” said Hecht. “I usually get to know the students who sit in the front row of my class pretty well, but not those in back. In recent years, I tried to get around that by walking around Taylor during class. But the faces on Zoom are closer, which is kind of cool. It’s still about connecting with your audience.

“I’m doing things that I wouldn’t do in a normal year,” he added. “For instance, on a Power Point slide, I’m scribbling. I’m writing on it. I’m trying to make it more of an ‘I’m here with you’ feeling than I normally would. And I think it’s working.”

First-year student Francesca Pauca came to Princeton as a sociology major. But she likes her CHM 201 course so much that she is considering a switch to chemistry or pre-med. Before each class, Pauca goes through a small ritual to prepare – she gets a cup of coffee, reads through the textbook, and notes questions she plans to ask. She enjoys watching faces pop up on Zoom as students log in.

“I think it’s incredible that my professors and my TAs, especially in the chemistry department, have worked so hard to make this a good experience,” Pauca said. “I’ve never had this much work, that’s for sure; but I’ve also never been this engaged in my classes. I guess I thought that when things went remote, I wouldn’t be that engaged. But I’ve been very pleasantly surprised to see that, wow, this is still amazing. It’s still Princeton.”

Paul Chirik, the Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Chemistry, teaches Honors Introductory Chemistry this semester synchronously from his office with a webcam and a blackboard. He couples these with asynchronous lectures that feature him writing out notes and narrating as he goes. He plans to continue asynchronous teaching for the “mathematically heavy” portions of his class so that students can go back over the material at their own pace. But prep time for teaching has nearly doubled, he said. And he misses the interaction with students.

“The virtual format is really challenging for them to ask questions,” Chirik said. “Because they are first-year students, they have not been on campus and likely not had a college class before. All of this is daunting.”

CHANGES GOING FORWARD

Marissa Weichman, assistant professor of chemistry, joined the chemistry faculty this summer and thus took up a new position and a new kind of instruction all at once.

“Teaching CHM 305 remotely this semester will likely change the way I teach moving forward,” said Weichman. “I lectured using an iPad both to show slides and write material out by hand. Being able to switch between slides, handwriting, and showing other multimedia made my lecturing more dynamic than it would have been standing in front of a chalkboard.

“Being forced to get creative with my teaching was a really valuable exercise, and I will certainly continue to use these techniques when we return to in-person teaching.”

Robert L’Esperance, director of undergraduate studies, has worked closely with Jon Darmon, lab manager for Chirik and Brad Carrow, to develop the technological framework for many courses. In her own turn, Lecture Demonstrator Kathryn Wagner has recorded over 127 videos for the semester, such as Hydrogen Balloon Explosions, Thermite, and Magnetism of Liquid Oxygen. Recordings of course material provide an opportunity for multiple viewings, she said. In addition, the video presentations give each student a front-row seat.

Many of these videos are likely to remain in circulation even after a return to traditional teaching.

Still, it’s obvious what everyone is missing.

“The missing parts for online instruction are the informal pre- and post-lecture Q&As and the chances to gain perspective from other students,” said Wagner. “Most of the professors miss interacting with their students.”

Francis added, “We really did try to do our best so that 99% of the skills transfer to the students. Not having the lab part means that they could focus on the conceptual part, so that’s nice. But it’s not the same.

“Mostly,” Francis said, “we just miss being in the lab.”