Visiting Faculty Research Partnership Racks up Another Gold Medal Summer

In a program that continues to prove its worth to Princeton Chemistry faculty and visitors alike, the Visiting Faculty Research Partnership (VFRP) wrapped up earlier this month following a summer of collaborations with institutions from around the country.

Faculty members from Emmanuel College, California State University San Bernardino and Hampton University—all of which have moderate-to-small research programs—spent three months at Princeton Chemistry with a couple of their undergraduate students. They worked on projects that form the core of their research at home but enjoyed a special focus here with faculty, graduate students, and postdocs at Frick Lab.

The VFRP program, now in its third year, sponsors nine weeks of partnered research, networking, group meetings, mentoring, and presentations along with academic enrichment workshops run by Susan VanderKam, associate director undergraduate program and director of diversity programs. The VFRP program culminates in a Summer Symposium, where each participating student presents a research poster.

Here are our 2024 VFRP faculty members and their students.

From Emmanuel College

Located in the Fenway area of Boston, Massachusetts, Emmanuel College is a private Roman Catholic college founded as the first woman’s college in New England, although today it is a coeducational institution. Assistant Professor Juan Duchimaza Heredia from the Department of Chemistry & Physics brought two students with him this summer and partnered with William S. Tod Professor of Chemistry Greg Scholes and the Scholes Group.

P.I. Juan Duchimaza Heredia, standing; (left to right) and Emmanuel undergraduates Megan Reilly and Gwyneth Gagnon.

Duchimaza Heredia’s lab explores polymer quantum dots to understand the mechanism behind the optical properties that allow them to fluoresce, with consequent applications in bioimaging, LED sensors and screens, and forensics.

“This summer we looked at just the polymer by itself to see if there is any correlation between the size and what color it either absorbs or fluoresces,” said Duchimaza Heredia. “We generated a geometry and then used computational chemistry methods that take the unfolded carbon dot and then tried to find out what is statistically the more likely arrangement of atoms. That’s what we took as our starting point.

“What was really great about being here with the Scholes Group this summer is that it exposed me to a lot of new methodologies. And then I also had a chance to reach out to Annabella Selloni, because I had a lot of questions about the best algorithmic programs to consider. It was really great to be exposed to what else is out there.”

Undergraduate Gwyneth Gagnon is interested in pursuing forensics after graduation. The chance to do summer research at Princeton Chemistry introduced her to graduate student work. “We don’t go to an institution that has a grad school, so living the everyday life of a grad student, drinking black coffee and seeing them take breaks and then work all day and living that life – it helped broaden my horizons.

“We also did work with ChemDraw and PowerPoint. I’ve just learned so much this summer about being a chemist.”

Megan Reilly particularly enjoyed the opportunity to watch a Final Public Oral in Taylor Auditorium. “These graduate students are doing very high levels of research, and seeing how the student approached his talk and what he felt he needed to share so people could understand the outcome was very helpful.”

From California State University, San Bernardino

At CSUSB, a public research university outside Los Angeles, Assistant Professor of Chemistry Joyce Pham designs new hybrid solids with both molecular organic and inorganic structural motifs. Together with her two undergraduate students, she partnered with the Cava Lab this summer.

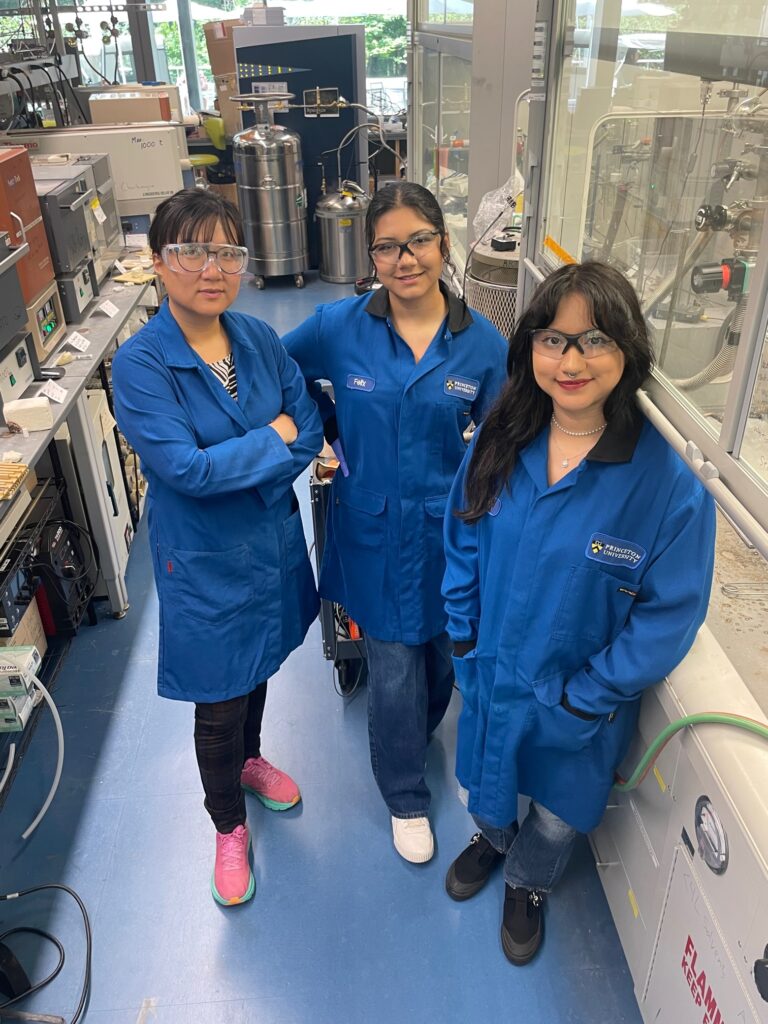

P.I. Joyce Pham and CSUSB undergraduates Katherine Aguilar and Lesly Gonzalez.

“At CSUSB, I am the students’ primary resource for discussion of solid-state chemistry research because it is rather a niche field. At Princeton this summer, the students had a plethora of people with whom they could consult, from graduate students in the group to postdocs, and even other faculty with analogous interest in the field,” said Pham.

“The multiple levels of guidance that my students received were impactful. I was grateful to be among a community of solid-state chemistry teacher-scholars. And it is obvious to me the level of thoughtfulness that Susan VanderKam puts into designing the summer program.”

Undergraduates Katherine Aguilar and Lesly Gonzalez worked alongside the Cava Group on replacing one inorganic portion of a known extended solid with an organic molecular feature to achieve an inorganic-organic hybrid material. The Cava Group has previously investigated other systems involving the 3d transition metals, which formed the scientific foundation for this partnership. The research this summer examined other phase spaces involving 4d and 5d transition metals with the goal of discovering general principles to guide further hybrid materials discoveries.

“Back home we’ve only had time so far to focus on the synthesis, but during the summer not only did we learn new ways to optimize our synthesis to get our desired products, but also learned how to analyze what we made,” said Aguilar.

“I guess the biggest takeaway I got this summer is that there’s just so much to learn at these different levels. Me and Lesly were learning alongside Teresa (Lee) and Dr. Pham, just coming up with new stuff as we go.”

Gonzalez said she appreciated the fact that Ph.D. candidates really get to burrow into one project, made obvious by her summer here. “A big thing that me and Katherine were wondering about was how we could maximize our time here,” she said. “One of the things we did was arrive really early and sometimes stay really late. But also, you have to take time for yourself, too, and get away from all of it so that you can just reflect on what you have done.”

From Hampton University

Graham Chakafana, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at Hampton University, joined VFRP this year for the second time, partnering with the Kleiner Lab. His students, Dillon Bethea and Keziah Harris came back, too, sharpening not only the research skills they learned last summer but engaging the “soft skills” essential to a community of researchers.

Hampton University undergraduates Keziah Harris and Dillon Bethea with their P.I. Graham Chakafana.

“This time around was actually a lot easier for me in terms of the research,” said Harris. “I knew a lot of the instruments and what to do with them already. And then presenting my research was a lot easier for me as well. Last year, I was really nervous because I never had an internship before and never presented about my research before.

“I was surprised at the growth that I’ve had throughout the two times of being here. I felt like I wasn’t just representing myself, but Hampton University and my professor, too. That was a huge weight on me, but it made me work even harder. It really taught me a lot about myself. I’m a fighter, and I will keep working hard at something until I learn how to do it. Knowing that is one of the things I loved most about being here.”

Bethea added: “Last year, it was a surprise to find myself in a lab setting with so many brilliant minds. That’s something I’ve always dreamed of. I’ve always said to myself, I want the highest form of education. I want to be in a room full of smart people and be part of them. So being in that atmosphere was nothing short of a blessing.

“Any student that comes through this program should not be afraid to ask questions,” he said. “It’s definitely intimidating. You don’t want to ask because people are busy. Everyone’s working. But we’re undergrads for a reason. We’re still learning and trying to see where we fit in. It was great because everyone would just stop what they were doing to help you out.”

Chakafana said this second summer project allowed the group to fill in some gaps left open at the end of last summer. Their research focuses on understanding nucleotide metabolism pathways in Plasmodium falciparum. This is the parasite that causes malaria. Determining the structure of the protein that keeps it alive may give researchers a leg up on therapies that can selectively thwart the parasite in the human body.

“I just have to thank the chemistry department, because this program is very important for students,” said Chakafana. “This is our second time here, and they are now thinking of the Ph.D. as an option. It was never an option when we started. Dillon was getting into dental school or nothing. There was no Plan B or Plan C. It’s something I always tell my students: don’t just have one plan because if it fails you’ll be devastated. And you need to be exposed to people who are doing other things before you can think about the options.

“That’s one of the things my students got here this summer. I loved seeing them grow.”